LARGE SYSTEM ARCHITECTURE:

Policy Design for

Public Education,

Healthcare, and

Government

Our central idea is to redesign the incentives in large systems . . . we call this "System Redesign"

“Organizations tend to behave the way the structure and incentives of the larger system in which they operate rewards them to behave. If you don’t like the way they’re behaving, change the larger system structure and incentives to reward the behavior you want.”

— Walter McClure

Problems have causes . . .

Public policy too often has a hard job getting to the heart of the problem. The public, and therefore the policy-makers, tend to define problems in terms of what they see: ineffectiveness, unresponsiveness, resistance to change, the influence of special interests, corruption . . . so tend to think solutions lie in changing the people in charge, in ‘better management’, in regulation.

But that is simply attacking symptoms. Problems have causes . . . so real solutions lie in finding what’s causing the problem, and in fixing that.

Experienced consultants have found the central challenge in working with an organization is the resistance of those in charge to accepting a rigorous diagnosis of the problem. Often that means a failure to get the incentives set right. The incentives are in the system design. Those in the institution take the current system as a given. So redesign requires an initiative from the political leadership and from the civic sector outside.

. . . So we think about the architecture of large systems.

The Theory of Their Design

First, understand that the behavior of organizations in education, health care etc. is shaped by the incentives built into the ‘macrosystem’ in which they operate.

Second, find the features of the current macrosystem that need to be changed, to alter organizational behavior; the ‘front log’. Follow Hirschman’s advice about “starting with the change that creates the most pressure for other constructive changes”.

Third, decide what you want the future macrosystem to look like.

Fourth, implement. Get a ‘lead architect’, organizational and individual. Give that architect independence, and stable financing. Understand, the change will take time; must be staged. Intellectual leadership might be as important as legislation.

Cases of Successful System Redesign

We are applying the strategy of redesign to three large systems.

Education

In this system, existing in state law, legislatures and governors are gradually withdrawing the old public-utility arrangement; enabling entities other than the local district to offer public education and enabling to families to choose.

It is a transition from the old public-sector public utility to an open, competitive – yet public – elementary/secondary system.

The country is in a transition, too, from system change through centralized planning to a process of innovation-based change, with teachers given real authority to shape the program of learning in the school.

Healthcare

There is market failure in what is now commonly referred to as ‘the health care system’. But the proper response is not – as is often thought – regulation . . . because there is regulatory failure too and regulatory failure is worse because so much harder to correct.

The proper response to market failure is market redesign. Its central idea is simple: Identify the high-quality clinics and hospitals and arrange the benefit programs to flow patients to these identified clinics and hospitals.

Government

Here again the states are the critical actors: They design and redesign the units of local government; they make many of ‘the rules’ that the shape the process of representation and electoral politics in the national government. Their constitutions require them to balance their budgets; they cannot operate a system of deficit-finance. The structure of public education exists in state law.

The huge entitlement programs – Social Security and ‘health care’ – are a national responsibility, but state legislative decisions are central to enhancing productivity in the operations of the ‘delivery system’ for state and local programs.

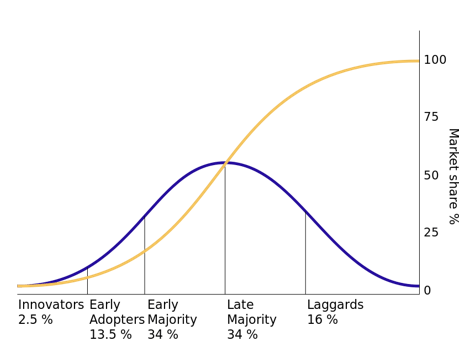

We think particularly about the 'how' of system change

Too many efforts have thought in terms of a grand transformation engineered politically; the old system replaced by the new-and-better. Realistically, the process is a more gradual one. The policy adjustments come gradually; the response of organizations in the institution spreads gradually.

Here is the general principle

Here is an example from Education